History of IEC

What is an International Eucharistic Congress?

The origins of the Eucharistic Congress

Born from a desire to deepen devotion to Christ in a changing world.

In the mid-19th century, following the convulsions of the French Revolution and in response to the rapid changes in society brought about by the Industrial Revolution, many Catholics felt the need to foster initiatives aimed at promoting reverence for the Eucharist. These initiatives placed at their core Eucharistic Adoration and a revival in a spiritual and theological appreciation of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

It is from within this historical context that Eucharistic congresses arise soon after 1870. The perseverance of a devout laywoman, Émilie-Marie Tamisier (1834-1910) played a key role in the creation of such congresses. She was the pupil of Saint Peter Julian Eymard (1811-1868) and Fr Antoine Chevrier (1826-1879), and she was supported by Bishop Gaston de Ségur (1820-1880) in her desire to hold a congress that celebrated and promoted the Eucharistic Mystery.

The aim was to unite devotion to the Most Holy Eucharist with large gatherings of the faithful. In this way, people would be made more sensitive to the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, while also recognising that they were not alone in their faith; that there were in fact vast numbers of Catholics who were committed to the same Eucharistic Lord.

In June of 1881 the first Eucharistic Congress was held at Lille, France. Besides faithful Catholics from France and Belgium, delegations were welcomed from eight other countries. The organisers were so taken with the success of the congress that they decided to set up a commission to ensure the continuity of the movement. Their work included planning the framework of future congresses, such that they would always include lectures, personal testimony, large-scale opportunities for worship, and a Eucharistic procession.

One year later the second congress took place in Avignon, thanks to the support of the Confraternity of Pénitents-Gris (Grey Penitents). In 1883 Archbishop Doutreloux of Liège received the participants of the congress, and in the Belgian city a solemn procession was held, which served as a visible sign of the vast scale of respect for the Eucharist, as intended by the organisers.

The fourth congress met in Fribourg, Switzerland, in 1885, under Bishop Mermillod. The congresses thereafter returned to France: to Toulouse (1886) and next to Paris (1888), followed by Belgium again (Antwerp 1890).

Early growth and the first international gatherings (1880s–1900s)

The first congresses take shape and expand across Europe.

Pope Leo XIII regarded the Eucharist as the ultimate sacramental expression of Catholic unity and, in accordance with his request, the eighth congress took place in Jerusalem in 1893. The Pope was represented by an official legate, Cardinal Langénieux, indicating the importance of the event and the Holy Father's aspirations for unity.

The election of Pius X, 'the Pope of the Eucharist', opened up a new phase in the history of Eucharistic congresses. While an increasing number of the faithful participated in these congresses, emphasising their international nature, there also emerged a connection with the growing liturgical movement.

The correspondence between these two movements highlights the fundamental relationship between the Church and the Eucharist, as well as the ideal of ‘active participation’, as stressed by the Motu Proprio of Pope St Pius X, Inter Sollicitudines (1903). Moreover, Eucharistic congresses served to illustrate and support the contemporary papal magisterium regarding frequent reception of Holy Communion and that age at which children might receive First Holy Communion.

While the first fifteen Eucharistic congresses took place in French-speaking countries, in 1905 the congress was called to Rome by Pope St Pius X. Following the congress in Tournai (1906), the next three congresses were held in countries which had Protestant majorities: Metz, which was part of Germany at that time (1907), London (1908) and Cologne (1909).

In 1910 the congress crossed the seas for the first time, and it was hosted by Montreal, in Canada. The rapid growth of the congresses, and the increasing numbers of foreign delegates, meant that their public impact was growing. This was particularly the case for the congress of Madrid (1911) and at the congress of Vienna (1912), where imposing Eucharistic processions made a strong impression on public opinion.

After the First World War, the tradition continued with the congress of Rome (1922). During the period between the two World Wars the congresses emphasised positive witness to the Christian mystery of faith.

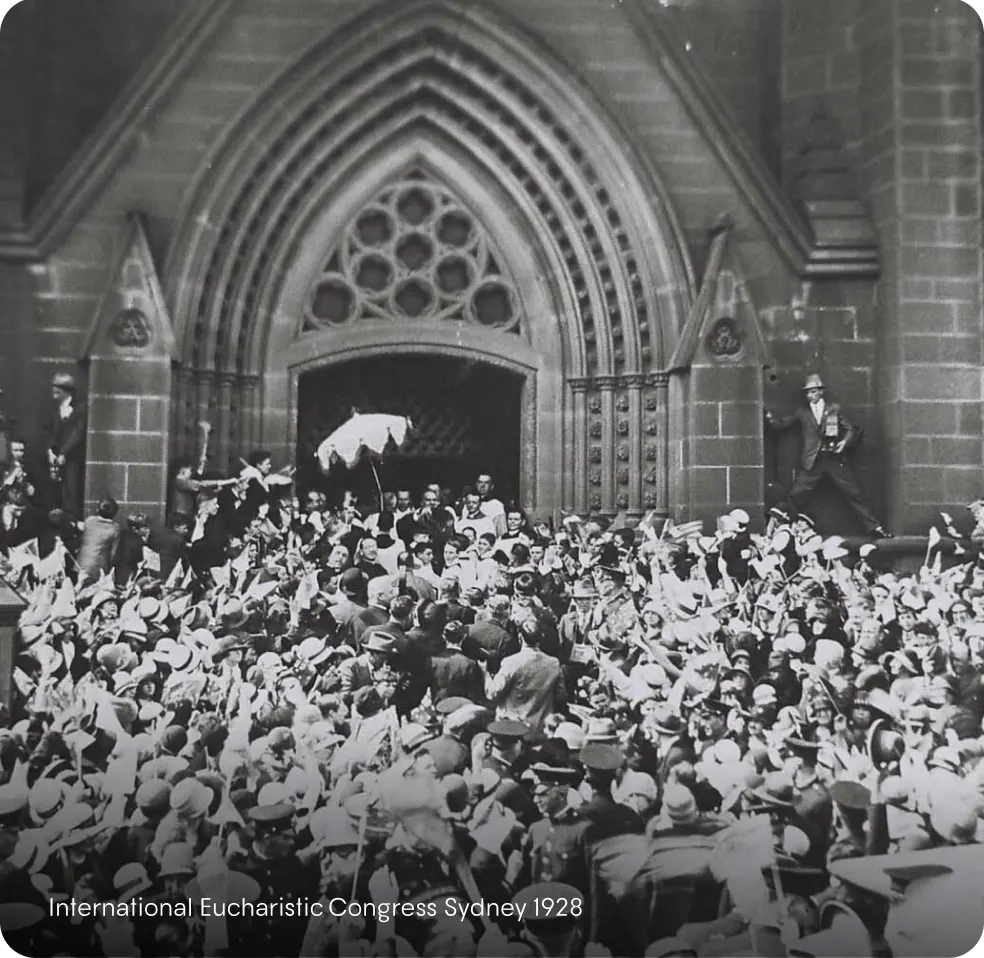

The 1928 Sydney congress

When Sydney hosted one of the largest religious events in the nation's history.

This was evidently the case at the 1928 congress in Sydney. The congress opened with the consecration of the newly completed St Mary's Cathedral and included the largest religious spectacle seen in Australia at that time: the Blessed Sacrament borne by ship from Manly Cove to Circular Quay, while five biplanes flew overhead in the shape of the Southern Cross and a crowd of people in boats across the harbour joined in passionately singing 'O Sacrament Most Holy'.

The Blessed Sacrament was then processed through the streets of Sydney, with both the secular and Catholic press estimating the crowds for the event at over 500,000 people.

Post-War to the modern era (1940s – Today)

How the congress evolved in a changing, modern world.

After the Second World War, the connection between Eucharistic congresses and the liturgical movement became ever more fruitful, with the Mass being placed more and more at the heart of events. The congress in Munich in 1960 is emblematic of this development where, thanks to Cardinal Doepfner and a group of learned theologians, all manifestations of respect towards the Eucharist began to be seen together with the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

During the period following the Second Vatican Council, international Eucharistic congresses in Bombay (1964), Bogotá (1968), Melbourne (1972), Philadelphia (1976) and Lourdes (1981) continued to reflect the joys, pains, and needs of the contemporary world, and offer the hope provided by our Eucharistic Lord.

The universal values of family, peace and freedom, and the need for new evangelisation, were at the heart of Eucharistic congresses in the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. These congresses ranged all over the world: from Nairobi (Kenya, 1985) to Seoul (Korea, 1989), Seville (Spain, 1993), Wrocław (Poland, 1997), Rome (2000, Holy Jubilee Year), Guadalajara (Mexico, 2004), Quebec (Canada, 2008), Dublin (Ireland, 2012), Cebu (Philippines, 2016), Budapest (Hungary, 2021) and Quito (Ecuador, 2024). In recent years, congresses have explicitly emphasised the connection between the Eucharist and the universal mission of the Church.

The Statutes for the Pontifical Committee on International Eucharistic Congresses clearly state the reason for its existence: To make Our Lord Jesus Christ in his Eucharistic Mystery ever better known, loved and served, as the centre of the life of the Church and of its mission for the salvation of the world.'' (art. 2)

Pope Leo XIII, who approved those statutes in the late 19th century, himself seems to have had a particularly 'Eucharistic' faith. The final encyclical he wrote before his death, Mirae Caritatis, was on the topic of the Eucharist and was published on the Vigil for the feast of Corpus Christi in 1902.

In that text he noted the, 'beautiful and joyful spectacle of Christian fellowship and social equality which is afforded when people of all conditions, gentle and simple, rich and poor, learned and unlearned, gather round the holy altar, all sharing alike in this heavenly banquet.' (n.11)

It is our firm intention that precisely such a 'spectacle' should dazzle all who attend the congress in 2028.

In a world that is rife with division, the startling sight of a great multitude from all walks of life – and all parts of the globe – receiving with shared reverence the Blessed Sacrament is one that should cause many observers to stop in their tracks and, hopefully, it is also one that will draw many back to the altar of the Lord.

Indeed, it may awaken in some a desire to join us at the foot of the altar for the first time.